Welcome to the Newsletter Series. Ivy and I co-wrote a periodic newsletter together and this piece is adapted from an edition of it, dated when the newsletter came out.

The Dream

Becoming a chef is a dream of mine that had me questioning my career as an engineer lately. This trip was a perfect chance to prototype working in the kitchen, so since the beginning I’ve been looking at when to make it happen. It was tough to find the time since most restaurants require you to work for a few months at minimum, which would be a huge opportunity cost for the rest of our plans. Finally an opportune moment came: a friend had connections in Hong Kong to restauranteurs that were willing to take me under their wings very short term and Ivy had plans for herself in nearby Shenzhen.

Through the connections, and later their connections, I got to work as a line cook in two kitchens — 11 Westside, a high end Mexican restaurant, for three weeks (one of the owners was on The Final Table) and Checkin Taipei, a fast casual Taiwanese restaurant, for one week — as well as be a barback at the Wilshire, a speakeasy, very briefly.

My expectations going in were that the pay would be low, the hours would be long, it’d be hard to schedule meeting up with people since I’d be working when others were eating, I’d get yelled at a lot, and I’d be thoroughly exhausted everyday. On the upside, I was hoping I’d get to learn how to cook like professionals, gain insights on the pain points within kitchen operations, and feel the same satisfaction I’d previously felt during my very limited exposure to working kitchens (a day spent in the Google kitchen and a night helping a friend with her dumpling popup).

The satisfaction I’m talking about is unlike anything else I’d experienced elsewhere. There’s a nonstop adrenaline rush that’s stimulating both physically and mentally. You’re frantically running around while also concentrating on how to execute each step of a dish perfectly. And at the end of the day, there’s something like a runner’s high from the chaos being over and from seeing happy customers satisfied by something you created with your own hands.

The Reality

Working in a kitchen was everything I expected it to be and more. My first day at 11 Westside, I came in all keen, observing and analyzing everything. They made all the tortillas, salsas, and marinades from scratch, there was so much to learn. The kitchen space was huge, they had all sorts of fancy equipment like giant stand mixers and heat lamps. There were dedicated dishwashing staff, handling my least favorite part of cooking, and an endless supply of clean towels for every spill and hot handle which got replenished by a laundry service whenever we ran low.

The expected downsides were no joke, the exhaustion was particularly real. Halfway through my first day I was already far too tired to think anymore. Every night after a shift, all I’d have energy to do was watch some mindless TV. Not only that, my feet would be throbbing, I’d barely be able to stand. What helped was getting new shoes. Never would I have imagined I’d become a wearer of Crocs, but it turns out as ugly as they are, the company really knows their target demographic’s needs.

On the other hand, all my hopes were also met. I’ll be applying what I learned in a professional kitchen to my own cooking in the future and I’ve got several ideas for startups based on the pain points I observed. Ping me if you want to talk more about either of these, they’d be whole essays on their own. As for the aforementioned satisfaction, I felt it almost everyday. Whenever the dinner rush came in, it was an endless battle to stay afloat. There was almost no time for emotions, but whenever I did have a moment of pause, the feeling was there.

An unexpected upside was the strong sense of community. 11 Westside felt like a family. A super diverse family with people from over 12 different countries as well as across the entire LGBT spectrum. Almost everyone was tattooed, and almost everyone smoked.

It’s hard to place a finger on what exactly makes a culture work, taking out any single person would not make or break it, but I think many small factors contributed. Everyday at ~4:00pm one of us would cook a staff lunch for everyone else to eat together. We had dedicated ingredients and equipment, like a wok, for people to showcase their own home flavors. I had some of the best adobo fried rice of my life here. After closing, any leftovers would be brought out for staff to share. Sometimes a cook would make a little extra near the end of the night to ensure there would be some (not enough to hurt the bottom line, but enough to make tired and hungry employees happy). People rotated playing their music in the kitchen so you got to hear a lot of different cultures. They could be hilariously goofy yet also seriously hardworking when service got intense.

It felt so tight knit, yet jarringly it’s also a very transient family. In my short time there, two other cooks left. Some people were there for the money — it’s a well paying job for those without much education, some were there for the passion, some were there because it’s the only life they’ve known. Kitchen Confidential captured the feeling really well, I’d recommend giving it a read if you’re interested in hearing more about the life of a cook.

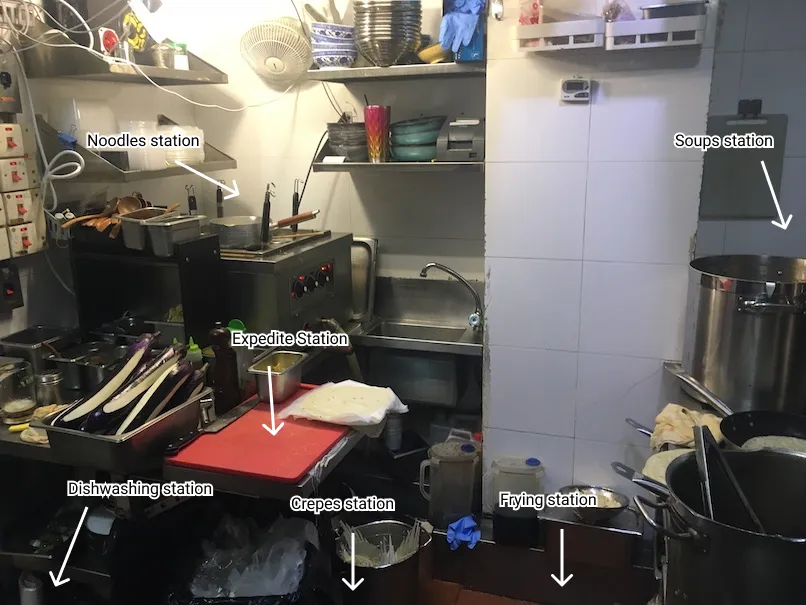

Checkin Taipei turned out to be a complete 180 flip. As a fast casual restaurant, the focus was affordable yet interesting food. The menu was mainly noodles and egg crepe (蛋餅). The kitchen was a third the size, at any given point there was half the staff, an order size was on average half the price, yet they generated almost the same monthly revenue as 11 Westside. You can do the math on how many more orders are being cranked out in that case.

Because the food had to be prepared faster with less manpower, many of the recipes used pre-made ingredients that required little prep. Most of the job was just assembling things together. All the cooks were locals speaking to each other in Cantonese. Staff lunch was catered. We had to clean our own towels at the end of the shift and leftovers got thrown out. Basically just about everything was different.

This is not meant to be a criticism of Checkin Taipei, none of these are bad things, and this is the reality of what most small restaurants’ operations are like because of limited space and staff. It was just a shock how different the culture was. I was exactly looking for what a different kind of kitchen is like and I got it.

And Checkin Taipei’s food is actually really tasty! The salt pepper chicken is some of the best I’ve had. Check it out if you’re in Hong Kong.

The Future

I could definitely see myself working in a kitchen long term, but only if I sacrificed a lot of other things I’m not willing to. For now, I’m happy to go back to my privileged tech life, taking away many lessons learned from this month.

Throughout my time I screwed up a bunch — sometimes I cooked things for too long and others for not long enough. One day I screwed up making the batter for desserts and we didn’t have any left to serve. At first I took much too long to cut vegetables and to plate dishes. My first Caesar Salad took me 30 minutes because I kept screwing up the hard boiled egg.

I’m never going to be mad again at a restaurant for taking too long because it very well could be that they tried their chances on someone like me. Or because there’s a flurry of tickets and the POS system sucks, causing the tickets to be mixed up. Or because something dramatic happened and now they’re short staffed. Or because it’s a dish like roast chicken or seafood congee which has a time consuming step that must be done at time of order (in fact it’s sketch when those come out fast, unless it’s a restaurant dedicated to the one dish, constantly cranking them out).

Personally, I also found working in a kitchen to be great character building. When you’re getting yelled at for something that went wrong, it’s so easy to want to deflect the blame, especially when you’re not directly at fault. It took practice and reflection to start taking accountability. Also, the intense services were a great test in handling stressful situations as well as trying to maintain order in chaos. If you have all the ingredients prepped for every dish as well as have backups of everything for when you run out, the service will run smoothly. But reality is often not like that, you’ll have not enough of one thing or another and you’ll have a half-prepped container calling you to finish it, and it’s a bunch of judgment calls on when is the right time to be doing what.

An Aside on Bars

I asked to help a bit at the Wilshire to see what bartending was like. I had no expectations going in and I knew next to nothing about how to mix drinks.

I worked as a barback, prepping ice and garnishes, washing cups, and other miscellaneous tasks. A friend came in and ordered a drink, so they actually let me make that one drink! I got practically every step wrong in some way, much feedback was provided.

It turns out bartending is everything I do not like about cooking. It’s closer to baking, you have to be very exact with your pours and shakes or else the drink tastes incorrect. And a bartender has to do all the other jobs, at least at a small speakeasy, like dishwashing, talking to customers, taking orders, settling bills. Basically all the tasks I appreciated being handled for me in the kitchen.

Especially since I’d be doing bar shifts right after a kitchen shift, I stopped after just one night.

I do now have a much better appreciation for the job as well as for cocktails though. It’s a tough gig with a lot of multi-tasking and attention to details.

Some small lessons:

- Any bar that pours from various hoses into a cup, you better just be there to get drunk. Those are not real drinks.

- Neither is anything with vodka in it. Vodka is boring to taste. Gins on the other hand are very interesting with all sorts of different notes in them. Next time you’re at a bar, ask for a Negroni, then ask for another made with a different gin. You’ll be surprised by how different they taste despite having the same ingredients.

- Know that if you’re sitting at the bar, the bartender hears everything you say, even if they don’t intend to. It’s almost impossible not to eavesdrop.

This has been a wonderful month that passed by way too fast. I’m extremely grateful for Jon for connecting me to his friends and for Kelvin and Jacky for letting me work in their restaurants and living out my dreams.

I can safely say this was beyond my expectations and I’m already a bit nostalgic about the experience. Til next time Hong Kong.